by Beth Levine | Aug 13, 2018 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking

It doesn’t take much to be a good leader-communicator. Perfection may be elusive, but being good enough to earn the admiration of your team are well within reach. Adherence to a few core principles takes care of most situations.

In my book Jock Talk: 5 Communication Principles for Leaders as Exemplified by Legends of the Sports World, I walk readers through the philosophy behind, and application of, these 5 principles: Audience-centricity, Transparency, Graciousness, Brevity, and Preparedness.

In my book Jock Talk: 5 Communication Principles for Leaders as Exemplified by Legends of the Sports World, I walk readers through the philosophy behind, and application of, these 5 principles: Audience-centricity, Transparency, Graciousness, Brevity, and Preparedness.

Taken together, they send two really important messages about you to your audience: 1) that you care about and respect them, and 2) that you’re real and therefore credible and trustworthy.

Audience-centricity is probably the most fundamental of the five principles. Simply put, audience-centricity is making the audience’s interests and experience a top priority in the planning and execution of a talk. Too many speakers prepare and deliver what is important and interesting to themselves without enough careful consideration of their listeners. Being audience-centric is a mindset shift that encourages the speaker to prepare and deliver content in a way that will matter to and resonate with the audience.

Transparency is exactly what you think it is; it’s about being open and direct—yes, and honest, too. Transparency is critical. It contributes to the levels of sincerity and trust that are accorded to you by your audience.

Graciousness is the art, skill, and willingness to be kindhearted, fair, and polite. As motivators and influencers, love and peace work far better than hate and war. Speaking in positives rather than negatives leaves lasting, favorable impressions.

Brevity is a crowd-pleaser and needs no further introduction.

Preparedness speaks for itself as well, especially because the unprepared speaker is the one who is most likely to be longwinded, not to mention unfocused. While the mere thought of preparation might bring on feelings of dread or even impossibility, there are ways to prepare that take only seconds but that can greatly enhance a speaker’s effectiveness.

As summer winds down and everyone settles in for the homestretch toward year-end, I would encourage you to pick one of these principles as your personal pet project for the fall. Which one of these 5 do you feel like you need to improve on the most? Or which one of these 5 would have the most impact on your business if you strengthened it? Pick one and go for it!

by Beth Levine | Nov 14, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking

If I had a dollar for every time I told a client, “well, that’s really not what this event calls for, attendees are coming for a celebratory occasion not a lecture” or “it’s not really your place to be talking about the speaker’s topic, you’re simply introducing them” or “what you’re describing you want to talk about is more appropriate for an external audience rather than an internal one,” I could retire!

Speakers and presenters veer out of their lanes all the time. It’s as though an invitation to make a few remarks confers responsibility for the entire event on them. Or they feel as though, given the opportunity, they need to be as comprehensive as possible. Not so.

Speakers and presenters veer out of their lanes all the time. It’s as though an invitation to make a few remarks confers responsibility for the entire event on them. Or they feel as though, given the opportunity, they need to be as comprehensive as possible. Not so.

Here are 3 tips to help you stay in your lane:

1. Know your job. For every occasion when you need to speak, you have a “job.” By job, I mean a communication task: you might need to motivate, persuade, reassure, inform, update, or even introduce. There’s always a verb that describes your job, you might even have a primary and a secondary job. Knowing your job helps you paint the boundary lines of your lane. As you prepare your remarks, all you need to do is test what you’re planning to say against your job and stay inside those boundary lines.

2. Be #audience-centric, have perspective. Have you ever been to a fundraising gala, basically a party, where everyone is dressed up, having fun, socializing at tables with friends, and then the buzzkill comes – long narratives from the microphone about the organization’s serious work (and let’s be honest here, no one’s paying attention)? Yes, the work is important and yes, there’s a captive audience; but no, now’s not the time for the laundry list of “what we do.”

Or, have you ever gone to hear a special speaker and the person who introduces them not only delivers a nice intro, but then offers their own spin or summary on the speaker’s topic? To be polite, this is not only unnecessarily repetitive but it’s also not what the audience came to hear. To be less polite, this is inappropriate, often making audience members impatient and annoyed.

Perspective is key to staying in your lane. Perspective requires you to be audience-centric – to put the audience’s needs and experience ahead of your own. Without it, you risk alienating the audience.

3. Err on the side of #brevity. When in doubt, be brief – no one has ever annoyed or alienated an audience by being brief. If you’re not sure of your job or your lane, put your energy and efforts into being short and sweet. Sometimes speakers swerve out of their lanes because they’re not clear on who is supposed to say what and they want to make sure they cover everything. I hear you, I get it. Still, either coordinate with the other presenters ahead of time and/or let your audience ask you if they need more.

At the end of the day, it’s all about them – your audience. Stay in your lane so you don’t hit them!

by Beth Levine | Oct 30, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking

I want to share a personal story that’s not entirely flattering. In fact, the episode was a little bit jolting at the time, but soon thereafter it reaffirmed two important aspects of my coaching and training philosophy:

When it comes to audiences, always connect with them and always learn from them.

So, here’s the story …

A few years back, I was invited to be the guest speaker at an open house for a Toastmasters chapter. It wasn’t a regular Toastmasters meeting, it was a membership cultivation event. I was asked to speak on the importance of having a big idea and how to identify and articulate one.

I’m a fan of Toastmasters and, in fact, recommend it to clients who need lots of practice speaking, usually to desensitize them to the fear of public speaking. The event was quite interesting, it drew a very diverse crowd of people, and the Toastmasters members and leaders were very welcoming. I gave my talk, which I had prepared ahead of time (I always prepare ahead!), I kept it brief (I always try to be brief!), and there was a robust Q&A.

When I was done, I got great feedback and lots of thank you’s from the audience. However, on my way out the door at the end of the event, one of the chapter leaders approached me with his clipboard. Apparently, he had been scoring me while I was speaking, and it turns out I didn’t do so well by Toastmasters’s standards. He had counted um’s and ah’s (thankfully there weren’t too many), and he had timed, measured, and scrutinized me for public speaking metrics that weren’t on my radar screen.

When I was done, I got great feedback and lots of thank you’s from the audience. However, on my way out the door at the end of the event, one of the chapter leaders approached me with his clipboard. Apparently, he had been scoring me while I was speaking, and it turns out I didn’t do so well by Toastmasters’s standards. He had counted um’s and ah’s (thankfully there weren’t too many), and he had timed, measured, and scrutinized me for public speaking metrics that weren’t on my radar screen.

Admittedly, I went in unfamiliar with the methodology of Toastmasters. Still, my initial reaction to the sudden appearance of the clipboard felt like a breach of hospitality – that without any forewarning, an invited guest would be scored and critiqued? I was taken aback, and my ego was bruised. I recovered quickly, though, and my reflection on the experience reaffirmed two things for me:

First, with all due respect to Toastmasters, being an effective speaker is less about precision and more about being real and connecting with people. In my practical experience, being real and accessible goes a lot farther than pitch perfect delivery. Audiences are pretty forgiving and they’re also hungry to be let in, to feel like they know and can identify with the speaker – warts and all.

Second, that we can always learn from our audiences and, in reality, we always do. Every interaction with a client and every speaking engagement informs and sharpens my approach. I always say that my clients are my greatest teachers. The trick is to look for those lessons, be open to them and consciously make a note-to-self about what you plan to do differently or better next time.

To this day, I encourage clients to try Toastmasters – for nerves, um’s and ah’s, and just for muscle practice. It’s all good. Nonetheless, there’s a good case for authenticity over accuracy, and there’s also a good case for letting others teach you, even when it’s unexpected or uncomfortable.

by Beth Levine | Oct 2, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Last week, I lost my voice. Literally, I couldn’t talk. Laryngitis.

Naturally, I joked about it: The ironies of a communication coach not being able to speak – what good am I in this condition? What a pleasure and relief for my family – finally, a break and some much-wished-for silence! My own vocal chords were on strike – was it something I said?

I also wondered. When will it come back – a day, a week, longer? Who am I without my voice? Am I relegated to communicating digitally only? What did people with laryngitis do before texting and emailing?

I will admit, sudden onset of laryngitis prompted some panic and an existential crisis: Whoa, where did this come from, what did I do to bring this on? What would I do if I had to deliver a speech or presentation in this condition? Cancel, reschedule, or create a killer PowerPoint or video? How could I turn this seemingly negative event into a positive? (Maybe blog about it?) My livelihood depends on my voice, what would I do if this persisted?

Turns out, I was still me; I had the same thoughts, ideas, and feelings. I just couldn’t share them – vocally, that is. It also turns out, the people around me were at a little bit of a loss without the all-too-familiar sound that drove through my larynx – my news, my bad jokes, my unsolicited opinions and everything else I rattle off in the course of a day. It was quite interesting to observe how people reacted to my inability to speak, including the pharmacist who, perhaps in an attempt to empathetically mirror my limitations, gradually dropped his own voice to a raspy whisper to answer my barely audible questions.

The experience made me think about voice and the fact that it’s not my voice that I lost, it was only my ability to talk. I couldn’t talk. But I had a voice and could give voice without being able to make much sound. I could communicate. So as with any other change that occurs in life – for the better or the worse – I decided that, if this stayed with me, I would adapt. I would still communicate and spread my ideas (like the gospel of #audience-centricity!) through writing. Maybe I would work on another book and share my thoughts that way instead of through speaking engagements? Maybe I would become a speechwriter, creating the actual words for speakers instead of coaching them to formulate and deliver their own? Either way, not being able to talk was not going to be the end of me.

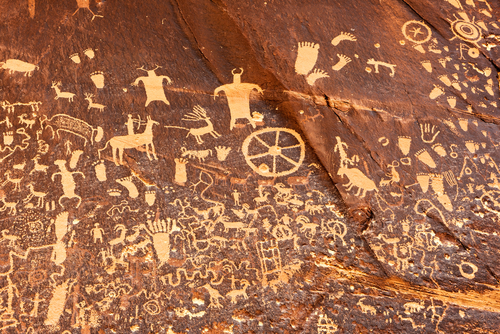

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

P.S. About two days later, my voice returned – albeit not in fighting condition and still on the mend. Nevertheless, existential crisis averted and lesson learned: I never lost my voice and I never will.

by Beth Levine | Apr 4, 2017 | public speaking

Universal experience: You patiently sit through a talk in which the speaker drones on for 30 minutes just to make a point that clearly could have been made in five.

Arrrrggggh, frustrating! You feel like your precious time was wasted. And that’s because your time was, in fact, wasted. This is where phrases like, “well that’s an hour of my life I’ll never get back” come from.

Arrrrggggh, frustrating! You feel like your precious time was wasted. And that’s because your time was, in fact, wasted. This is where phrases like, “well that’s an hour of my life I’ll never get back” come from.

And this is why brevity is one of SmartMouth’s 5 communication principles for leaders.

If you’re a speaker or presenter, consider this: You want to be that person, the one who is able to be concise and impactful. Being brief is the fastest and best route to being memorable and impressive.

Brevity is cultivated, and here’s what it’s all about:

-

It’s about planning and preparation – yep, knowing how you’re going to open, what your main points are, and where you want to take your audience so you can do it efficiently.

-

It’s about rehearsal – yep, and by rehearsal, I mean talking out loud so you can hear for yourself where you need to clarify, cut, or refine transitions.

-

It’s about respecting the unspoken agreement between you and your audience that you’ll use their time wisely and deliver value to them.

-

It’s about respecting the agreed-upon time limits you were given.

-

It’s about avoiding TMI and limiting your information dump to only those things that will be interesting to your audience (and not just to you).

#Protip #1: Ask yourself whether your audience is in the room by choice or by obligation. If it’s by obligation, do everyone a favor and be brief!

#Protip #2: Brevity trumps comprehensiveness 99.9% of the time!

Up to this point, I have made my point in 282 words (only 10 more words than the Gettysburg Address). Hopefully, it’s short enough to hold your attention and long enough to leave you with valuable food for thought!

In my book Jock Talk: 5 Communication Principles for Leaders as Exemplified by Legends of the Sports World, I walk readers through the philosophy behind, and application of, these 5 principles: Audience-centricity, Transparency, Graciousness, Brevity, and Preparedness.

In my book Jock Talk: 5 Communication Principles for Leaders as Exemplified by Legends of the Sports World, I walk readers through the philosophy behind, and application of, these 5 principles: Audience-centricity, Transparency, Graciousness, Brevity, and Preparedness.

Speakers and presenters veer out of their lanes all the time. It’s as though an invitation to make a few remarks confers responsibility for the entire event on them. Or they feel as though, given the opportunity, they need to be as comprehensive as possible. Not so.

Speakers and presenters veer out of their lanes all the time. It’s as though an invitation to make a few remarks confers responsibility for the entire event on them. Or they feel as though, given the opportunity, they need to be as comprehensive as possible. Not so.

When I was done, I got great feedback and lots of thank you’s from the audience. However, on my way out the door at the end of the event, one of the chapter leaders approached me with his clipboard. Apparently, he had been scoring me while I was speaking, and it turns out I didn’t do so well by Toastmasters’s standards. He had counted um’s and ah’s (thankfully there weren’t too many), and he had timed, measured, and scrutinized me for public speaking metrics that weren’t on my radar screen.

When I was done, I got great feedback and lots of thank you’s from the audience. However, on my way out the door at the end of the event, one of the chapter leaders approached me with his clipboard. Apparently, he had been scoring me while I was speaking, and it turns out I didn’t do so well by Toastmasters’s standards. He had counted um’s and ah’s (thankfully there weren’t too many), and he had timed, measured, and scrutinized me for public speaking metrics that weren’t on my radar screen.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of  Arrrrggggh, frustrating! You feel like your precious time was wasted. And that’s because your time was, in fact, wasted. This is where phrases like, “well that’s an hour of my life I’ll never get back” come from.

Arrrrggggh, frustrating! You feel like your precious time was wasted. And that’s because your time was, in fact, wasted. This is where phrases like, “well that’s an hour of my life I’ll never get back” come from.